Why Executives Embrace AI While Workers Resent It: Profits Claim Productivity Gains

“Individuals who ignore the lessons of history are destined to relive them.” These words come from George Santayana, the esteemed Spanish-American philosopher who shone as a prominent Harvard professor before relocating to Europe and emerging as a pivotal public thinker. His profound writings offered guidance and clarity amid the bleakest periods of the two World Wars and the brink-of-disaster crises of the mid-20th century—a scenario that influential investor Ray Dalio anticipates could resurface in the coming years.

A History Lesson

Perhaps it’s an opportune moment to revisit the initial phases of the industrial revolutions, during which the workforce endured profound changes akin to what Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang and other leaders have labeled as the current AI-driven transformation, often termed the AI boom.

During the early 1800s, groundbreaking inventions such as the spinning jenny and the steam engine dramatically altered Britain’s economy and rapidly influenced global markets. Traditional mills transformed overnight, churning out unprecedented volumes of goods. Productivity levels skyrocketed in manners that even contemporary historians struggle to quantify accurately. In stark contrast, compensation for workers stayed remarkably flat for over half a century—a period economic historian Robert Allen dubbed “Engels’s pause,” honoring Friedrich Engels, the German industrialist and thinker. This stagnation in wages fueled widespread frustration and intellectual critique regarding capitalism’s trajectory, resonating deeply with the concepts Engels developed alongside his collaborator Karl Marx in their seminal work, The Communist Manifesto.

Remarkably, a similar wage stagnation phenomenon appears to be unfolding once more, precisely two centuries later.

For many years, economic expansion failed to translate into meaningful enhancements for those directly handling the machinery. Industrial magnates amassed staggering fortunes as innovative factories proliferated across the countryside, yet laborers endured grueling 14-hour shifts in cramped, hazardous environments with scant alternatives for employment. The substantial benefits stemming from technological advancements predominantly flowed to capital owners. It was only after the emergence of entirely new sectors—such as typing pools and telephone operations—that required more specialized skills, coupled with evolving political frameworks to address these shifts, that worker wages began to climb in tandem with productivity metrics.

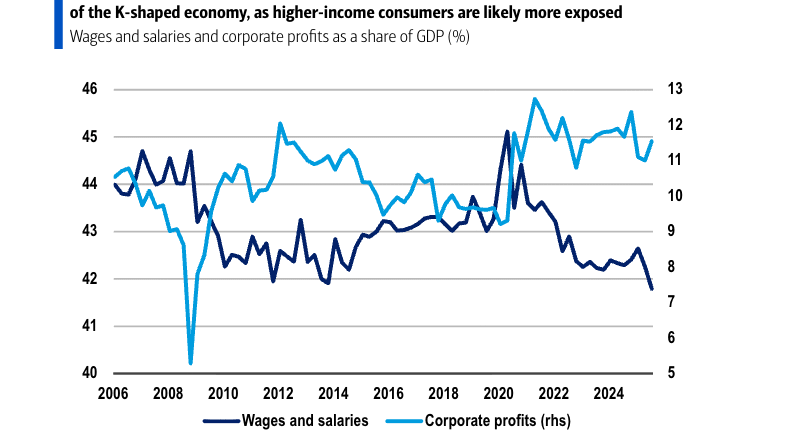

Today, economists detect unmistakable parallels to this historical pattern within the contemporary U.S. economy. Researchers from the Bank of America Institute have issued cautions that the latest surges in productivity are predominantly bolstering corporate profit margins, while wages and salaries are claiming a diminishing portion of the overall GDP. “Profits are gaining ground versus wages,” these economists observed, elaborating that “recent productivity gains have been piling up as corporate profits, with labor income steadily falling as a share of U.S. GDP.”

“It remains to be seen whether wages and salaries recoup some of their lost ground relative to corporate profits,” the researchers noted thoughtfully.

This development aligns closely with forecasts from Albert Edwards, the renowned analyst at Societe Generale, celebrated in financial circles for his sharp wit, memorable quotes, and consistently pessimistic market outlooks. Back in 2022, he suggested this could herald “the end of capitalism.” In a recent November interview with Fortune, he reaffirmed his position, especially concerning the explosive growth in corporate profits amid what he termed the “greedflation” period, and cautioned that a “day of reckoning” looms around the mid-decade mark.

Such shifts occur against a backdrop of a U.S. economy presenting mixed signals. Revised data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics reveals that the nation added just 181,000 jobs in 2025—a figure so modest it hovers near statistical insignificance and pales in comparison to the 1.46 million positions created in 2024. Nevertheless, overall economic growth has proven resilient. Bank of America economists project approximately 2% annualized GDP growth for the fourth quarter, indicating that production levels are increasing even as employment expansion moderates.

When combining these dynamics, the implications are clear: elevated productivity per employee.

Whether these productivity improvements stem solely from AI remains uncertain. Bank of America points out that the uptick in productivity commenced around the pandemic era, well before the debut of ChatGPT. Contributors to this early boost might include the widespread adoption of remote work arrangements, heightened digital integration across operations, and reductions in workforce sizes through strategic layoffs. Numerous specialists continue to question AI’s transformative effects on the labor market, now three years post its mainstream emergence.

That said, in recent weeks, analyst perspectives have noticeably evolved. Discussions of an AI “takeoff” have proliferated rapidly online, while markets witnessed a sharp sell-off, erasing nearly $1 trillion in value from software company stocks, driven by apprehensions that AI could supplant engineering roles more swiftly than expected. Over the weekend, Erik Brynjolfsson, a foremost Stanford researcher, published an essay contending that the United States is transitioning from the intensive investment stage of artificial intelligence toward a “harvest phase,” wherein prolonged expenditures begin yielding tangible productivity enhancements. His projections indicate that U.S. productivity growth approximately doubled in 2025 relative to the average of the preceding decade.

“The productivity revival is not just an indicator of the power of AI,” Brynjolfsson emphasized. “It is a wake-up call to focus on the coming economic transformation.”

An Economy of Resentment and Profit Hoarding

Nevertheless, this economic transformation elicits far from universal approval—quite the contrary. Initial skepticism regarding AI has intensified into outright animosity among the American workforce. Surveys reveal that most Americans harbor deep fears about AI, with minimal enthusiasm reported, even from those who identify as technological optimists. Employees feel aggrieved by mandates to adopt a tool that essentially mirrors their workflows and innovations, positioning itself to displace them in the foreseeable future. A Gallup poll indicated that six out of every 10 Americans express distrust toward AI, and a broad consensus supports the necessity of stringent regulations to prioritize AI safety and data security.

Conversely, corporate executives—as a group—remain exhilarated by AI’s prospects, yet they appear oblivious to the depth of negativity among their teams. A Harvard Business Review survey uncovered a stark disparity: 76% of leaders believed their staff were enthusiastic about AI implementation, whereas only 31% of frontline workers shared that sentiment.

The divergence highlighted in Bank of America’s analysis may partly explain this perceptual gap. The majority of workers have yet to experience tangible upsides from the AI-driven stock market surge; instead, they contend with a sluggish job market and elevated costs due to tariffs persisting throughout the year. Higher-income brackets, shielded by equity appreciations and property assets, maintain steady consumption patterns, but spending by lower and middle segments is decelerating noticeably.

“For now, higher profits relative to wages are yet another driver of a K-shaped economy,” the Bank of America report concluded, underscoring how these imbalances exacerbate economic polarization.