CEOs Reveal AI’s Minimal Impact on Jobs and Output, Reviving 40-Year-Old Paradox

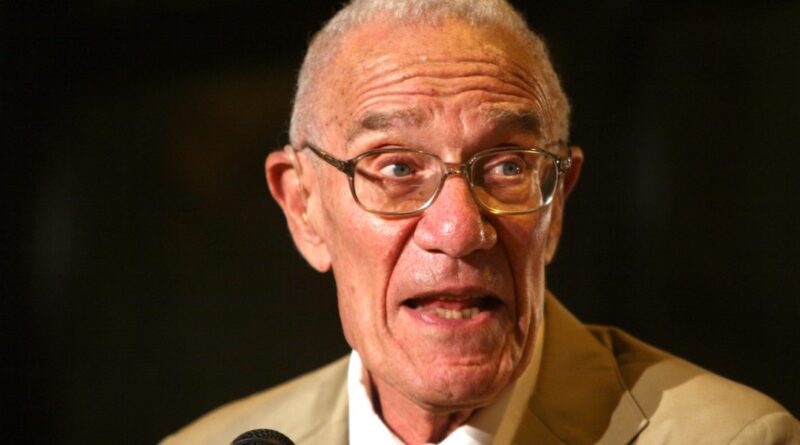

Back in 1987, renowned economist and Nobel Prize winner Robert Solow delivered a pointed commentary on the sluggish advancement of the Information Age. After the introduction of transistors, microprocessors, integrated circuits, and memory chips during the 1960s, both economists and businesses anticipated that these groundbreaking innovations would transform workplaces and spark a dramatic rise in productivity. Contrary to those expectations, productivity growth actually decelerated sharply, falling from an average of 2.9% between 1948 and 1973 to just 1.1% in the years following 1973.

These cutting-edge computers, rather than streamlining operations, sometimes overwhelmed organizations with excessive data output. They churned out excessively detailed reports that required printing on vast quantities of paper, leading to inefficiencies. What was heralded as a revolutionary boost to workplace efficiency turned out to be a significant disappointment for several years. This surprising development earned the moniker Solow’s productivity paradox, stemming directly from the economist’s famous remark about the disconnect.

“You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics,” Solow famously stated in a 1987 article for the New York Times Book Review.

Recent insights into how top executives are engaging—or failing to engage—with artificial intelligence reveal striking parallels to this historical pattern. This repetition challenges the bold assurances from economists and leaders in the tech industry regarding AI’s transformative effects on work environments and the broader economy. Even though 374 S&P 500 companies referenced AI during their earnings discussions— with the majority portraying their adoption as wholly beneficial—a Financial Times analysis covering the period from September 2024 to 2025 indicates that these optimistic implementations have yet to translate into measurable productivity improvements across the economy.

A fresh study released this month by the National Bureau of Economic Research examined responses from approximately 6,000 CEOs, CFOs, and other senior leaders at companies participating in business outlook surveys across the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Australia. The findings revealed that the overwhelming majority of these executives perceive negligible effects from AI on their daily operations. Although roughly two-thirds of the leaders indicated some level of AI utilization within their organizations, this involvement equated to merely about 1.5 hours per week on average. Furthermore, a full 25% of those surveyed reported zero use of AI in their professional settings. The research emphasized that nearly 90% of the companies claimed AI has exerted no influence on either employment levels or productivity metrics over the past three years.

That said, corporate leaders continue to hold high hopes for AI’s future contributions to workplaces and the economy at large. The executives projected that AI could deliver a 1.4% uplift in productivity and a 0.8% expansion in overall output within the next three years. While businesses anticipated a modest 0.7% reduction in employment during this timeframe, surveys of individual workers suggested a contrasting 0.5% rise in job opportunities.

Solow’s Paradox Resurfaces

In 2023, researchers from MIT asserted that deploying AI could enhance a worker’s performance by almost 40% relative to those not leveraging the technology. Yet, as new data emerges without evidencing these anticipated productivity leaps, economists are increasingly questioning the timeline—or even the certainty—of returns on the massive corporate investments in AI, which skyrocketed beyond $250 billion in 2024 alone.

“AI is everywhere except in the incoming macroeconomic data,” noted Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo, in a recent blog post that directly echoed Solow’s decades-old insight. He elaborated that contemporary economic indicators show no traces of AI’s influence in employment figures, productivity measurements, or inflation trends.

Slok pointed out that, beyond the dominant Magnificent Seven tech giants, there are no visible indications of AI boosting profit margins or elevating earnings forecasts in other sectors.

Drawing from numerous academic investigations into AI’s productivity implications, Slok highlighted a landscape filled with conflicting conclusions about the technology’s practical value. For instance, last November, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis issued its State of Generative AI Adoption report, documenting a 1.9% rise in excess cumulative productivity growth since ChatGPT’s debut in late 2022. In contrast, a 2024 study from MIT projected a more tempered 0.5% productivity increment over the ensuing decade.

“I don’t think we should belittle 0.5% in 10 years. That’s better than zero,” remarked Daron Acemoglu, the study’s author and a Nobel laureate, during discussions at the time. “But it’s just disappointing relative to the promises that people in the industry and in tech journalism are making.”

Additional research sheds light on potential explanations for these muted outcomes. ManpowerGroup’s 2026 Global Talent Barometer, based on input from nearly 14,000 employees across 19 countries, reported a 13% uptick in routine AI usage among workers in 2025. However, trust in the technology’s effectiveness dropped by 18%, signaling ongoing skepticism and reluctance among the workforce.

Nickle LaMoreaux, IBM’s chief human resources officer, announced last week that the company plans to triple its hiring of young graduates. This move underscores a recognition that, even as AI automates certain entry-level responsibilities, failing to onboard junior talent could lead to shortages in future middle management ranks, thereby threatening long-term leadership development.

Prospects for AI-Driven Productivity

It’s worth noting that this current lull in productivity could yet turn around dramatically. The IT revolution of the 1970s and 1980s, after initial underperformance, ultimately fueled a robust productivity boom in the 1990s and early 2000s. This included a notable 1.5% acceleration in productivity growth from 1995 to 2005, reversing years of stagnation.

Erik Brynjolfsson, economist and director of Stanford University’s Digital Economy Lab, argued in a Financial Times op-ed that signs of such a reversal might already be appearing. He cited fourth-quarter GDP growth tracking at 3.7%, even as recent jobs data downwardly revised employment gains to 181,000. Brynjolfsson’s own assessments pointed to a 2.7% productivity surge in the U.S. last year, which he linked to the shift from heavy AI investments to actual realization of benefits—what he terms the “harvest phase.” Similarly, former Pimco CEO and economist Mohamed El-Erian observed that job creation and GDP expansion are decoupling, much like they did in the 1990s amid widespread office automation, partly due to accelerating AI integration.

Slok envisions AI’s productivity trajectory potentially following a “J-curve” pattern: an early phase of subdued results succeeded by rapid, exponential gains. He emphasized that the realization of these benefits will hinge on the tangible value AI generates across applications.

Notably, AI’s development trajectory already differs from that of its IT forebears. Slok observed that in the 1980s, IT pioneers enjoyed temporary monopolies with premium pricing until rivals caught up. In today’s AI landscape, however, intense rivalry among developers of large language models has made tools widely available at rapidly declining costs.

Consequently, Slok argues, the trajectory of AI-driven productivity will ultimately rest on businesses’ willingness to strategically adopt and embed the technology into their operations. “In other words, from a macro perspective, the value creation is not the product,” he explained, “but how generative AI is used and implemented in different sectors in the economy.”